Writing a library in Kotlin seems easy but it can get tricky if you want to support multiple platforms. In this article we’ll explore ways for dealing with this problem.

The State of Kotlin

Why would I write a library in Kotlin? you might ask. If you have been using Kotlin for a while now you might think that you have everything within the Java ecosystem and it is not necessary to write anything new in Kotlin (apart from the application you are working on).

While Kotlin started out as a JVM language now it can run on multiple platforms and you can even have isomorphic Kotlin in your project. As I have written about this before Kotlin now can be used with Gradle in place of Groovy, on the frontend and also in your backend projects.

With Kotlin multiplatform projects and Coroutines getting out of beta we now have everything at our disposal to write production-grade code which is independent of the platform (JVM, Javascript, Native) it runs on.

There is one thing which stands in the way though: the lack of mature multiplatform libraries. So if you want to help with this effort this article is for you.

So What is a Library?

Now that we decided to write a library it is useful to define what a library really is.

Note that this is just my opinion, I’m not an authority figure on the topic. Feel free to point out if I missed something or if you just simply disagree, in the comments section.

In my definition a library is

- Generic program code

- Written to perform a single task

- Bundled in a package

- And distributed to the public in this form

Apache Commons IO is a good example for this. We add it to our projects as a dependency, we use its functions but it doesn’t try to change how we structure our project or write our code.

What is Not a Library?

A framework! A good example for this is Ruby on Rails. It is a framework which specifies for you how to code and how to structure your project. In this article we’re going to talk about libraries.

Things to Keep in Mind

Whenever you sit down to write a library there are some general guidelines which are applicable in any domain, not just for Kotlin ones.

Keep Your API Small

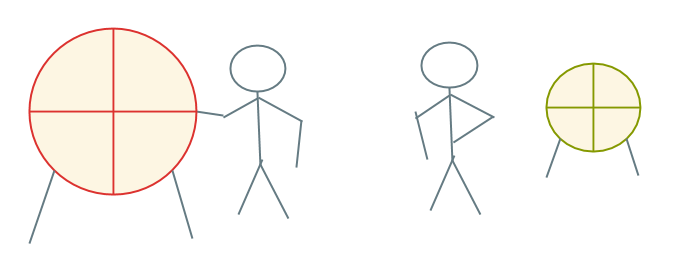

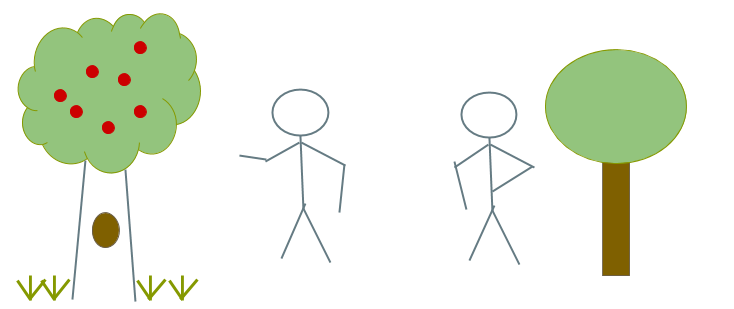

Giving an API to your users is similar to asking someone to hit a target with an arrow. The smaller the target, the harder it is to hit. This is true with libraries as well. The smaller the API you have, the easier it is to maintain, and you also minimize the chance that you accidentally expose something which you didn’t intend to. Take this API for example:

In the following examples we’re going to work on an imaginary library which exposes an API for handling UI widgets.

class MyComponent(

val isFocused: Boolean,

val children: List<MyComponent>,

val drawSurface: PixelGraphicsImpl) {

fun requestFocus() {

}

fun clearFocus() {

}

fun render() {

}

fun attachTo(container: Container) {

}

}

Here we expose the MyComponent class which has a property to tell whether it is focused,

it exposes its children, and also the draw surface which is used for rendering.

There are a lot of cases when you might have the feeling that you need to expose things because you think that it might be useful for you users. What actually happens most of the time is that you expose too much, your users start to rely on them and later when you figure out that some of the internals of your library need to be refactored you have to break the API for your users if you want to fix it. Let’s take a look at the same class with a smaller API:

class MyComponent(

val children: List<MyComponent>, // 1

internal val drawSurface: PixelGraphicsImpl) { // 2

fun requestFocus() {

}

fun clearFocus() {

}

internal fun render() { // 3

}

internal fun attachTo(container: Container) {

}

}

So after evaluating our class it turns out that

-

isFocusedwas not needed at all and we only want our users to be able to eitherclearorrequestthe focus. With this we preserved the same functionality but retained the ability to handle focus in any way we wish. -

drawSurfaceis something which we take as a dependency but it is internal to our library so we shouldn’t allow the external world to tamper with it. It happens quite often that users start to use things which you exposed in ways you didn’t intend it to work so this helps with that problem. -

It also turns out that

renderandattachTohad the same problem asdrawSurface: they are internal to the library and the users shouldn’t do rendering or component (re)attaching by hand.

Let’s take this a step further by introducing better abstractions.

Keep Your API Abstract and Clean

In the previous example we’ve cleaned up parts of our API and removed / hid some things which were not intended to be public. Now we’ll take a look at things we do expose:

class MyComponent(

val children: Iterable<Component>, // 1

internal val drawSurface: DrawSurface) { // 2

fun requestFocus() {

}

fun clearFocus() {

}

internal fun render() {

}

internal fun attachTo(container: Container) {

}

}

After careful investigation we concluded that:

- We don’t really need the functionality

Lists provide for ourchildrenand anIterablewill suffice. A good example for this is that if you expose aListof something which your users just want to iterate over with a for loop you either lose the ability to construct items on the fly or make it much harder to implement. With anIterableor aSequenceyou can do this easily. It also enables you to return an insanely high number of elements without filling up the memory. - As it turns out

PixelGraphicsImplis a concrete implementation ofDrawSurfaceand it has some internal things which we don’t want to expose. It can become problematic if we expose implementation classes through the API and make it impossible to change the implementation behind the scenes without breaking your users’ code.

all of these lead us to the realization that to clean up this mess we should start to…

Use Interfaces

By taking a hard look at what we have we can conclude that by exposing classes and concrete implementations through our API will lead to all sorts of problems, so using interfaces is a better approach overall:

interface Component {

val children: Iterable<Component>

fun requestFocus()

fun clearFocus()

}

class MyComponent(

override val children: Iterable<Component>,

val drawSurface: DrawSurface) : Component {

override fun requestFocus() {

}

override fun clearFocus() {

}

fun render() {

}

fun attachTo(container: Container) {

}

}

This way we are free to implement Component as we see fit. We can have any number of implementations

for it if we want and it won’t affect our users. An important caveat for this is to only return

abstract types from our factories:

object ComponentFactory {

fun createComponent(

children: Iterable<Component>,

drawSurface: DrawSurface): Component {

return MyComponent(

children = children,

drawSurface = drawSurface)

}

}

This might seem obvious, but this is often overlooked.

The Modularization Problem

So we separated our API and our concrete implementations into interfaces and classes.

The problem is that we can’t prevent our users from circumventing our clean API and using

MyComponent directly since Kotlin doesn’t have its own module system. What we can do

is to separate our packages into api and internal (or anything similar) and clearly

state in the documentation that everything in internal is subject to change:

// safe to use

package api

interface Component

interface DrawSurface

interface Container

// use them at your own risk!

package internal

class MyComponent : Component

class ThreadSafeComponent: Component

class PixelGraphicsImpl : DrawSurface

class DefaultContainer : Container

This solution is not perfect, but it helps.

Kotlin Tips

We’ve discussed a lot of things already, but we haven’t seen any Kotlin-specific tips yet, so let’s take a look at some.

Add a companion object

It might be a case that you don’t use companion objects in your project or you don’t have

the need for them in some API classes. What’s important to point out here is that companion objects

enable your users to define extension functions on your classes which can be invoked without

an instance. You can add an empty companion object:

interface Subscription {

fun cancel()

companion object

}

and your users gain the ability to augment your interface as they see fit:

fun Subscription.Companion.create(): Subscription {

TODO("Create new Subscription")

}

fun useIt() {

Subscription.create()

}

Take Extension Functions to the Next Level

Extension functions can also help you to create a more fluent API. Take a look at this example,

where our user has a list of Subscriptions:

val subscriptions: MutableList<Subscription> =

mutableListOf()

In order to cancel them all they most probably write something like this:

fun cancelAllSubscriptions() {

subscriptions.forEach {

it.cancel()

}

subscriptions.clear()

}

But what if we provide this functionality out of the box?

fun <T: Subscription> MutableList<T>.cancelAll() {

forEach {

it.cancel()

}

clear()

}

This way cancelAll can be called on any MutableList which holds Subscriptions:

fun usage() {

val subscriptions = mutableListOf<Subscription>()

subscriptions.cancelAll()

}

Have reified Functions Delegate Work

reified functions are very useful but they come with some caveats which are very frustrating.

One of them is that we need to use @PublishedApi if we want to access the internals of a

class. For this reason it helps greatly if we simply delegate the work from them to functions

which take KClass objects as parameters so we get the utility of reified functions

without the problems:

class EventBus {

private val subscriptions =

mutableMapOf<KClass<out Any>, (Any) -> Unit>()

inline fun <reified T : Event> subscribe(

noinline callback: (T) -> Unit) {

return subscribe(

klass = T::class,

callback = callback)

}

fun <T : Event> subscribe(klass: KClass<T>,

callback: (T) -> Unit) {

subscriptions[klass] = callback as (Any) -> Unit

}

}

Astute readers might spot the problem with this API. We’re not using interfaces!

Unfortunately interfaces don’t support reified functions, but there is a solution

which solves this problem:

Let reified Functions be Extension Functions

It is true that we can’t have reified functions in an interface:

interface EventBus {

fun <T : Event> subscribe(klass: KClass<T>,

callback: (T) -> Unit)

}

but we can have reified extension functions:

inline fun <reified T : Event> EventBus.subscribe(

noinline callback: (T) -> Unit) {

return subscribe(

klass = T::class,

callback = callback)

}

With this we get the best of both worlds, and usage stays the same:

fun usage() {

EventBus().subscribe<Event> { }

}

The tips above are applicable on any Kotlin project but there is a special kind of project which needs more care than a regular one:

Multiplatform Libraries

If you are working on a multiplatform library you need to write code which is idiomatic on all platforms. In the following section we’ll take a look at some tips which will help with this.

Use Properties Instead of Getters

Writing a getter (getX) for a property is not idiomatic in Kotlin. On the other hand

accessing fields in Java without getters is not idiomatic either! It turns out that

Kotlin properties are implemented in a way that both sides will see an API they

wish to see:

interface Position {

val x: Int

val y: Int

}

// idiomatic in Kotlin

pos.x

pos.y

// idiomatic in Java

pos.getX();

pos.getY();

Hiding a Kotlin API

Sometimes you have functions which look weird for Java users. A good example for this is

a lambda which has to return Unit. Having to return Unit for Java users is just weird.

Luckily we have some ways to hide things from Java users:

// reified is not visible from Java

class EventBus {

inline fun <reified T : Event> subscribe(

noinline callback: (T) -> Unit) {

// ...

}

}

// @JvmSynthetic was designed for this purpose

interface EventBus {

@JvmSynthetic

fun <T: Event> subscribe(eventType: KClass<T>)

}

// extension functions are not visible on the same class

inline fun <reified T : Event> EventBus.subscribe(

noinline callback: (T) -> Unit) {

return subscribe(

klass = T::class,

callback = callback)

}

This is nice but what if I want to…

Hide a Java API

Unfortunately there is no “official” way of hiding something from Kotlin users, but there is a hack which we can use:

class EventBus {

@JvmName("subscribe")

internal fun <T: Event> subscribe(eventType: Class<T>) {

}

}

internal functions are not visible for Kotlin users, but it is visible from Java.

There are some caveats though:

- This is a hack!

- Interfaces can’t have

internalmembers - We need to use

@JvmNamebecauseinternalfunctions have a funky name when we try to access them from Java

Extensibility

If you work on a library chances are that you want to design it for extensibility so your users can add their custom things. Take this interface for example, which we want to make extensible:

interface Position {

val x: Int

val y: Int

fun calculateArea(): Int = x.times(y)

}

The problem here is that from the Java side calculateArea won’t have a default implementation

only if we apply @JvmDefault to it. The problem is that this will only work with Java 8+

which might not be available (on Android for example).

So what we can do is to create base classes.

If we want a base class which doesn’t implement all members we can provide abstract

classes:

abstract class PositionBase : Position

If they do, an open class will do:

open class PositionBase(

override val x: Int,

override val y: Int) : Position {

final override fun calculateArea(): Int {

return super.calculateArea()

}

}

Just keep those functions final which you don’t want your users to override.

Multiplatform Annotations

Kotlin comes with some annotations which were designed to help with multiplatform

development. One of them is @JvmStatic which we can use to make members static

in the resulting Java bytecode, but it comes with some caveats:

interface Position {

val x: Int

val y: Int

fun calculateArea(): Int = x.times(y)

companion object {

@JvmOverloads

fun create(

x: Int,

y: Int = x): Position {

return DefaultPosition(x, y)

}

}

}

Note that in the past this was not usable in common projects but they were modified to be optional so we can now put them on any class regardless of the platform.

One of those problems is that we can’t use it in interfaces, not even on

companion objects defined in them.

A solution for this is to use objects and have them delegate to the functions

defined in an interface companion object:

object Positions {

@JvmStatic

@JvmOverloads

fun create(x: Int,

y: Int = x) = Position.create(x, y)

}

Multiplatform SAM Problem

Suppose that we have an interface which has a function which takes a lambda:

interface Observable<T : Event> {

fun onEvent(fn: (T) -> Unit)

}

If we want to use this from the Java side it is awkward:

// Oops! Function1 wanted!

observable.onEvent(/* */);

If we create a Listener interface to be used as a parameter:

interface Observable <T: Event> {

fun onEvent(listener: Listener<T>)

}

@FunctionalInterface would help here but we can’t use it in multiplatform common projects.

we won’t be able to use Kotlin lambdas here:

observable.onEvent(object : Listener<Event>{

override fun accept(event: Event) {

// ...

}

})

A solution for this problem is to keep the Listener interface and provide

Kotlin users with an extension function which accepts a lambda:

fun <T: Event> Observable<T>.onEvent(fn: (Event) -> Unit){

onEvent(object : Listener<T> {

override fun accept(event: T) {

fn(event)

}

})

}

This way it will be idiomatic from both Java and Kotlin.

How to Deploy?

So we now have a nice library which is idiomatic, easy to maintain and behaves well in multiplatform environments. The question is how to deploy it? As of the time of writing Maven Central and Bintray is hard to set up and the latter is not reliable. So what do we do? As it turns out there is a free service which works out of the box and deployment is as easy as creating a tag on GitHub: JitPack.

My suggestion is to use this until official tooling arrives for Maven Central releases.

Note that I’m not affiliated with JitPack in any way.

Conclusion

We’ve explored some of the intricacies of library development with Kotlin. It might seem hard to do at first but by following some simple guidelines it can become much easier with some practice. So armed with this knowledge

Let’s go forth and kode on!